The American Revolution, which ran from 1775-1783, had far reaching implications beyond its own shores and borders.

In Liberty’s Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World, Maya Jasanoff reminds us that about one third of residents in the 13 American colonies supported the British in the American War for Independence. In that sense, the revolution was akin to a civil war, and these British supporters were regarded as traitors by their fellow colonialists, the Patriots.

There were at least three groups, collectively called Loyalists, who supported the British. Whites who saw their interests aligned with that of the British, or who sought to preserve the life they knew or who felt the best future for the American colonies lay with Britain; Indian tribes such as the Mohawk and the Creek who believed their territories would be protected from further white incursion if the British won; and enslaved and freed Africans who believed the British promise that slavery would end for those who fought on Britain’s side.

All three groups lived in fear after Britain lost the war and the United States gained full independence. They feared for good reason. Some white loyalists were attacked, and their homes and properties destroyed or confiscated. More Indian lands were eventually taken over and incidents such as the infamous Trail of Tears remain horrible blots on American history. Many blacks, even those who were free before the outbreak of war, were enslaved or threatened with re-enslavement.

To escape their plight at least 60,000 loyalists – black, white and Indian – fled the United States. Jamaica was a primary refuge along with the Bahamas, Canada, Britain and Sierra Leone. Some ended up in Australia, India and elsewhere.

“Of all the British colonies to which loyalists migrated during and after the revolution, Jamaica presented the most immediately attractive destination,” writes Jasanoff. Their hopes rested on Jamaica’s opulence and wealth:

Sugar was gold in the eighteenth century. Jamaica’s trade in sugar and rum helped make the island the wealthiest colony in the late-eighteenth-century British Empire. On the eve of the American Revolution, when per capita wealth for a white person in England averaged £42, and about £60 for whites in the thirteen colonies, white Jamaicans enjoyed a per capita net worth of £2,201.

Jasanoff suggests that about 8,000 enslaved Africans, more than half of those who left the US, traveled to Jamaica, along with about 3,000 whites.

Loyalists – black, white and Indian – were disappointed not just with the loss of the war but the level of assistance they received afterward, though many received passage to Jamaica and other locations outside the US.

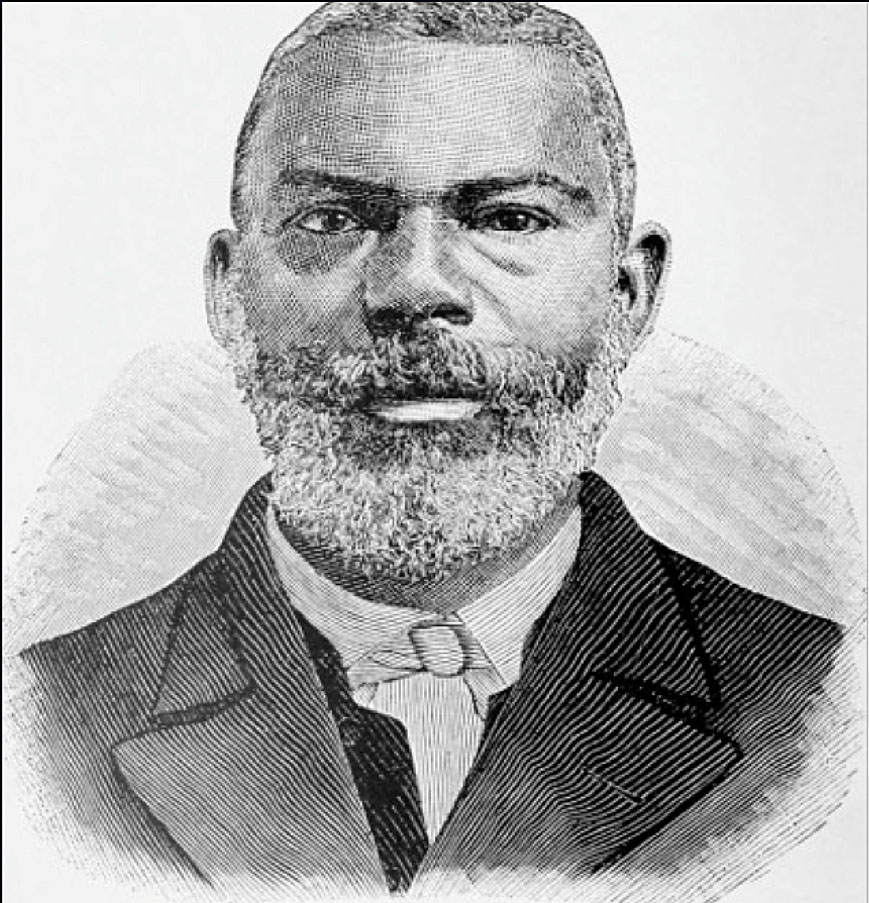

The bulk of such assistance went to white loyalists, many taking slaves with them. The British assisted a few freed blacks who supported them in the war. Among these was George Liele who, with his family, escaped to Jamaica after being threatened with re-enslavement after the American war. “The sheer demographic shock of Jamaica’s slave society must have struck black loyalist George Liele even before he disembarked,” Jasanoff says. “The very same ships that carried his family away from Savannah to a fresh start in freedom carried almost two thousand other blacks onward into continued slavery.”

Liele went on to establish Baptist witness in Jamaica, starting in 1783, after previously founding churches in Savannah, Georgia. This makes Liele the first known Baptist missionary. His chief associate, Moses Baker, was also an American émigré who initiated Baptist witness in western Jamaica. Leile and Baker were among the more prominent or well-known persons of African ancestry who escaped the US to Jamaica in consequence of the American Revolution.

John Pulis, writing in The Historical Encyclopedia of World Slavery, states:

Between July 1782 and November 1783, the British evacuated Wilmington, Delaware; Savannah, Georgia; Charles-Town, South Carolina; and New York City…. A small, but influential, number of blacks opted for transport to Jamaica. Among the more notable among these were Moses Baker and George Liele, folk or itinerant preachers who laid the basis for the island’s practice of Afro-Christianity.

According to Jasanoff, Liele’s presence and preaching proved a problem:

All that talk of equality in the eyes of the Lord, all that talk of the freedom in salvation – it sounded suspiciously like revolutionary language to slaveowners, who worried that missionaries might incite their slaves to revolt. And how much more they must have worried when those missionaries were black, and former slaves to boot.

Both Leile and Baker were imprisoned for simply preaching. Jasanoff recalls that “Moses Baker was arrested for quoting the words of a Baptist hymn:

We will be slaves no more,

Since Christ has made us free,

Has nailed our tyrants to the cross,

And bought our liberty.”

Writing in 1913, Wilbur Siebert provided details on some of those who traveled to Jamaica. “When, in December 1782, Charleston was surrendered to the Americans, 3,891 persons embarked for Jamaica, of whom 1,278 were whites and 2,613 were blacks.” He said, “A few others from West Florida, with their slaves, arrived in Jamaica during the summer of 1783, settling chiefly in Kingston, according to the parish records of that island.” About 5,000 black persons and some 400 white loyalists arrived from Savannah, Georgia.

The Jamaican assembly made provisions to assist the white loyalists:

The Assembly of the island passed an act for the benefit of all white refugees who had already come in, or should follow later, with the intent of becoming inhabitants. This act was made applicable to former residents of North and South Carolina and Georgia… who were paying the price of exile by being forced to relinquish their dwellings, lands, slaves, or other property.

The white refugees received extensive tax breaks:

It exempted these persons for seven years after their arrival from the payment of imposts on any negroes that accompanied them, as well as from all manner of public and parochial taxes, excepting the quit rents on such lands as they might purchase or patent. It also released them from all services, duties, and offices, except the obligations to serve in the militia.

The new arrivals led to a mushrooming of Jamaica’s population. Siebert noted:

The above facts help to explain the remarkable increase in population of Jamaica between the years 1775 and 1787. The census for the former year showed 18,503 whites, 3,700 free colored people, and 190,914 slaves; while for the latter year the figures are 30,000 whites, 10,000 free colored people, and 250,000 slaves.

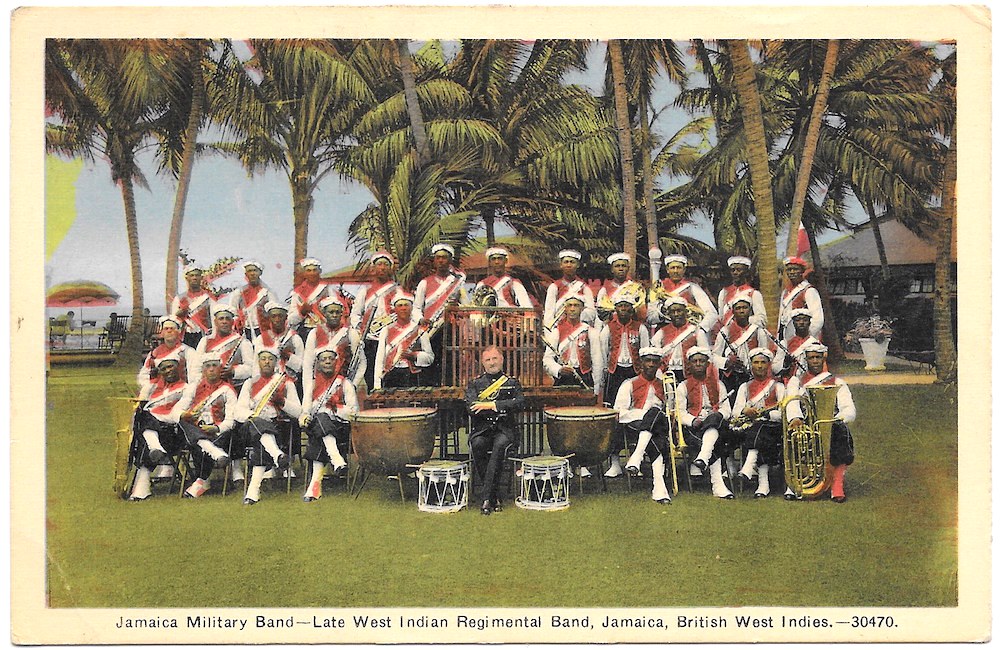

Jamaica Defense Force indicates that some blacks who traveled to Jamaica had joined its ranks:

The Jamaica Military Band has direct descent from the first of the old West India Regiments, which was formed in 1795 in the Windward Islands of the Eastern Caribbean. One of two units drafted into this regiment was the Black Carolina Corps, the remnant of a British loyalist regiment in the aftermath of the American War of Independence.

Jamaica proved a disappointment for the refugees. Land, their main source of hope, was scarce. In the absence of obtaining land, hopes of putting out their slaves to work for Jamaicans largely proved unsuccessful, as the island had more than 200,000 enslaved persons. Within a matter of a few months, provision made for them ran out. “The first large companies of loyalists who resorted to Jamaica were furnished provisions by the British government, but the supply soon proved inadequate,” said Siebert.

There was growing resentment among locals at loyalists’ tax-exempt status and the expense paid out to support them:

The justices and vestry of Kingston presented a petition to the Assembly…calling attention to the effects of the measure upon their parish…. The petition explained that there were nearly seventy housekeepers in the town of Kingston who were refugees, and hence were exempt from parochial taxes, although many of these were apparently wealthy and were engaged in commerce to a considerable extent. Others were tradesmen or mechanics in the exercise of lucrative employments. Some of these persons were occupying fine houses in the best situations in the town. Thus, the petitioners were deprived of the taxes that might have accrued from the “opulent refugees.”

Attempts to settle 183 white American loyalists in the parish of St. Elizabeth, most of them from the Charleston, South Carolina group, proved unsuccessful as the location was inhospitable. Records from a committee meeting states:

That it appears to the committee, from the several examinations taken before them, that certain parcels of land bordering on Black River, in the Parish of St. Elizabeth, commonly called the Morass Land, and laid out by Patrick Grant, surveyor, for the Refugees from America, cannot be drained for cultivation, but at such a considerable expense as to make it highly unprofitable that they will ever be drained. Passed in the affirmative.

Jamaican authorities refused to foot the bill to make the location habitable:

That it is the opinion of this committee, that certain lands in the Parish of St. Elizabeth stated to have been surveyed for the Loyalists from America, should not be patented at the expense of the island, and this House will not defray such expense, it having appeared in evidence that the lands are totally unfit for the purposes intended. Passed in the affirmative.

Indications are that slaves owned by American white loyalists in Jamaica were sold off and sent back to the United States and elsewhere. Some of the white loyalists left Jamaica, some even returning to the US.

It is interesting to determine which families in Jamaica – black and white – are descendants of these loyalists who fled the US during and after the revolution, and whether American Indian descendants are on the island.

Eron Henry is author of Reverend Mother, a novel. Ole Time Sumting blog was recognized with an Award of Merit by the Religion Communicators Council in April 2018

Engaging and enlightening. There were several former military companies that left America after the civil war for Trinidad. There are still villages in Trinidad named First, Third, Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Company. Second Company has disappeared, and one is uncertain whether there were others beyond the sixth. The people of African descent in these villages are known as Merikins (a corruption of “Americans”).

This is important work Rev. How come they didn’t teach us this in School or Sunday School?