By Eron Henry

Rastafarians in Jamaica suffered much from law enforcement, especially in the first 40 years of the movement’s founding.

Among the worst occurred in Coral Gardens in Montego Bay, St. James, in 1963. Attempts were made to evict Rastafarians from lands slated for hotel and tourism development. In April, violent altercations erupted between Rastas and police sent in to enforce the evictions. Several were killed. Others were arrested, detained and some tortured. The repression by the state spread to Rastafarian communities elsewhere on the island, continuing into July of that year.

Tensions were brewing for years. A state of emergency was declared in 1960 and several Rastafarians executed for allegedly plotting with communist Cuba against the Jamaican government.

These were the highlights of a general state of tension between the state, especially the police, and Rastafarians. Rastas referred to law enforcement and the structure that supported them as Babylon, an ancient empire and the biblical symbol of oppression.

Rastafarians were among the first to voice and demonstrate the brutality of Jamaica’s law enforcement. They had history as a witness. The Jamaica Constabulary Force (JCF) was formed in the wake of the Morant Bay Rebellion in 1865. Its intent was to protect the planters and merchants from the populace. To give security to those in power. To police agitated communities and groups. It was never intended to be a force on the behalf of the ordinary citizen. When the Rastafarian movement began in the slums of West Kingston in the 1930s, the JCF had the same mandate, the same mission, used the same protocols.

Countercultural

From the outset, the Rastafarian religio-social movement was countercultural in belief and practice. They drew inspiration from the countercultural Marcus Garvey, whom they recognized as a prophet. Garvey preached black independence and promoted a back to Africa campaign for blacks who lived in the diaspora.

They were influenced by Alexander Bedward, who broke from conventional Christianity and launched his own religio-social movement in the late 19th century, opposing the colonial system. Some of Bedward’s erstwhile followers were among the first Rastafarians, after his movement went into decline following his death in 1930.

Rastafarians believed in a black God and Christ whose origins were in Africa. And their sacrament was a form of hemp, ganja/marijuana. Its possession, and use, made illegal in Jamaica by statute in the 1920s.

Rastafarian men grew out their hair, long considered ill-bred among socially conscious Jamaicans. The men and women loced their hair, despised as unclean and uncouth.

Rastafarians promoted living in tight knit communities, like communes, farming fruits and vegetables and living close to the land. Among the more well-known is in Bull Bay, St. Andrew, just outside Jamaica’s capital, Kingston. Families were equal, with no elites, though there were elders as leaders. Males, however, would be dominant within households and could, theoretically, have more than one spouse. While not all Rastafarians were vegetarians, many were, eschewing the consumption of pork especially, and the preparation of meals with salt.

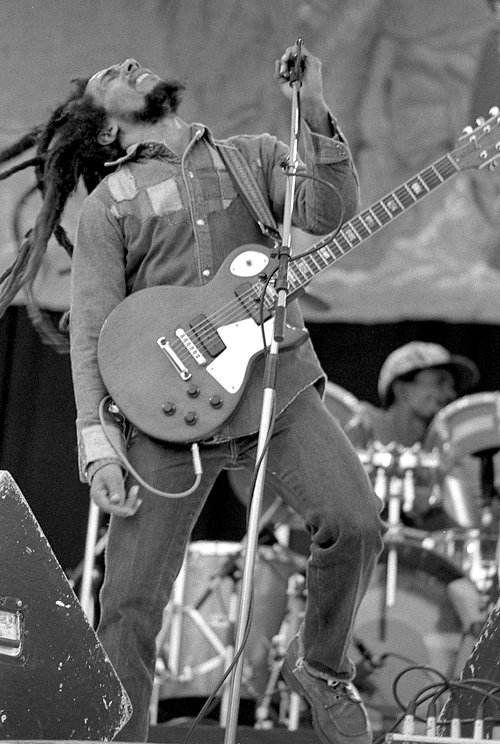

Rastafarians remained outside the mainstream, but the power and force of reggae music, which gained steam in the 1970s, opened space, grudging and slow, for entry into mainstream Jamaican life. Though some Jamaicans in the late 1960s and early 1970s dubbed it disparagingly as boom-boom music, reggae was too powerful, too universal, to be ignored or wished away. It is now Jamaica’s most well known and most valuable cultural export. Its major exponents, especially Bob Marley and the Marley clan, among the most famous Jamaicans.

One music critic claimed the basic beat of what became reggae music was sung by the enslaved in Christian churches in the 18th and 19th centuries. It resembled beats they knew and remembered from Africa. Missionaries from Europe, however, introduced music from that continent into local Christian congregations, and it gradually displaced the music the enslaved sung and danced to in worship. It was this beat Rastafarians captured and revived and helped to create a more modern sound. Reggae music, this music critic asserted, is essentially worship music.

Rasta culture embraced

The 21st century has seen a reversal of the wider society’s stance on Rastafarianism. Beyond reggae, aspects of Rastafarian lifestyle are being openly embraced, even celebrated. More black women are wearing their hair natural, without perm or the use of other chemicals, a throwback to the 1970s. Going beyond the style of the 1970s, the locing of the hair is now more common by both men and women not associated with Rastafarianism.

Doctors and scientists have long spoken of the ill effects of a high sodium diet. More and more persons are becoming vegetarians, and veganism has grown. Organic food is in high demand, with even the use of fertilizer frowned on.

By far and away the most surprising are attitudes toward ganja. Once criminalized, a growing movement is embracing its medicinal potency and value. Recreational ganja smoking, while not endorsed, is being more widely accepted.

A coup de grace for Rastas was the formal apology from the Jamaican government in 2017 for the 1963 repression. A JMD$10 million reparation fund was established for victims and their descendants.

Estranged and maligned, rejected and outcast, persecuted and brutalized, Rastas and what they believed and practiced have become mainstream.

Eron Henry is an ordained minister, public speaker, writer, editor and traveler. His novel, Reverend Mother, is available on Amazon. He can be reached at eronhenry2@gmail.com