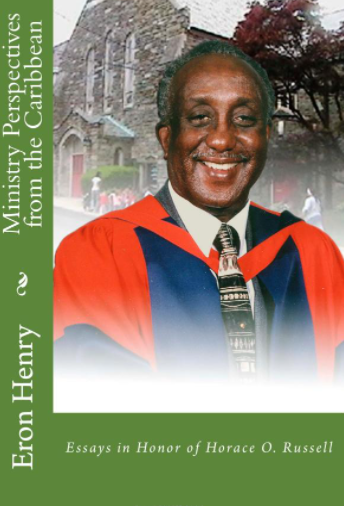

By Eron Henry

Dr. Horace Russell died on April 5, 2021, age 91. The following is a reprise from the book, Ministry Perspectives from the Caribbean, Essays in Honor of Horace O. Russell, published in 2010.

—

Horace Russell’s early life paralleled that of Jamaica’s rise from a colonial outpost of Britain into statehood. The son of a pastor, Russell yielded to the call to the Christian ministry. But it was a call couched within the context of a Jamaica trying to find its footing as a nation emerging out of colonialism into self government, and finally, into independence.

Hence, Russell’s own development mirrored that of the largest English-speaking Island in the Caribbean, whose citizens are notably vocal about rights, self rule, and independence. The fact that Russell is Baptist adds a distinctive flavor to his life and calling. Jamaican Baptists, historically, have played a central, some would say a unique role, along with the Moravians, in the country’s liberation movements. It began with the struggle to end slavery, continuing through the post-emancipation period, helping freed slaves to become independent peasants and merchants, and finally, forming the consciousness of an independent Jamaica.

Russell’s memory of his childhood was of one filled with happiness. “We never knew we were poor.” This lack of a sense of want came from a community spirit that existed. Neighbor helped neighbor, even in raring children. Peasant farmers assisted each other in planting and reaping. Churches and schools were built by a coming together of the community – all hands on board. Those who did not do construction work cooked and served meals.

Living in Jamaica’s small rural communities, Russell and his peers were largely untouched by the prejudices that prevailed in wider Jamaica. Ensconced in villages and districts where much of what was had was shared – food, labor, education, faith, wisdom – Jamaican peasants, as a group, developed a fierce independent spirit that, for the most part, had not encountered discriminatory practices. When this independent spirit met racial and class bias, they revolted.

This, partly, was behind Jamaica’s tumultuous struggle for statehood. The watershed year was 1938. A charismatic labor leader, Alexander Bustamante, and an astute political intellectual, Norman Manley, both cousins, formed a labor union and a political party, respectively, that challenged prejudicial notions and discriminatory practices that existed on shipping docks and the large sugar and banana plantations, where those who did not or could not do peasant farming, worked.

The labor union and the political party were aiming to win a struggle for estate and dock workers that the Jamaican church, notably Baptists and Moravians, had won a century earlier for peasants.

“Full Freedom” was achieved on August 1, 1838, after the British government compensated its slave owners with £20 million to free the enslaved. But slave-like conditions persisted, and in some instances, were worse than what prevailed during enslavement. Paid a pittance for wages, freed slaves were charged exorbitant amounts for rent for the same deplorable quarters in which they lived prior to emancipation. Working conditions were just as harsh, or only slightly better, than during slavery. Some were expelled from these properties as indentured workers were brought in from elsewhere, such as India and China.

Moravians, in a relatively small part of the island in the south-central region, and Baptists, over much of the rest, stepped in. The result was the creation of Free Villages. The formula was simple. Churches and pastors bought out whole or portions of estates, cut them into smaller lots (five acres or so), and sold these lots at bargain basement prices to the formerly enslaved. Ex-slaves built their own homes, often with community help, and planted their own crops, the surplus of which was sold in the markets.

The formula was revolutionary. These Free Villages became the backbone of much of Jamaican rural community life. Each village was self contained, though not isolated from the rest. Wherever there was a Free Village, there was a Baptist or Moravian church, and wherever a church was, there was a school. In some instances, health clinics were established.

Those who had not had the Free Village or independent peasant experience, or who abandoned the Free Villages for work on estates and on the docks, felt the pain of discrimination and exploitation. Not so Russell. Buoyed by this consciousness and experience while growing up in a resolute Baptist household – a Baptist pastor father and a Baptist teacher mother – Russell’s faith as a Christian mingled with a strong community independent spirit that would blossom into a Jamaican independent spirit.

But in some respects, Russell’s sense of independence was tempered by the aspirations of his father and mentor. Following in his father’s footsteps, Russell entered Calabar Theological College, the school where Baptist pastors and some teachers were trained. The older Russell connived with Keith Tucker, Calabar’s principal and Russell’s mentor, a British expatriate, to get him into Oxford University. Tucker’s aim, according to Russell, was to prove that a black boy could stand with the best of them at Oxford. Russell was the perfect candidate. Though happy go lucky, he was a brilliant student.

The elder Russell and Tucker enrolled Horace into Oxford and arranged his passage on a banana boat to England. Russell confessed that “I did not really want to go,” and that he knew little of the arrangements.

Burchell Taylor, one of Russell’s former students and one of the Caribbean’s foremost Christian intellectuals and church leaders, once described Russell as “bearing the brunt of being first in many things.” Horace Russell’s Oxford sojourn was the first of his many firsts – the first Jamaican Baptist, and one of the first Jamaicans, to be trained there.

Upon his return to Jamaica in 1957 with his young British wife, the former Beryl Redman, Russell became the first Jamaican-born tutor at Calabar. His return coincided with the quest for self government and independence by the island nation. By now, there were two political parties and two major trade unions that contended with each other, led by the two cousins, Bustamante and Manley, both later named National Heroes and revered as fathers of the nation.

Russell could not help getting caught up in the maelstrom. He joined the Students Christian Movement (SCM), and in time, became its general secretary, incorporating other Caribbean islands such as Haiti, the Bahamas, Trinidad and Tobago, and Barbados. In the 1950s and 1960s, the SCM became an intellectual haven for young members of the Caribbean intelligentsia. Russell rolls off names of young men who, in time, became who’s who in Jamaican and Caribbean intellectual, political, and religious life. Percival Patterson, former Jamaican Prime Minister, Dudley Thompson, a former minister of government and ambassador, Hector Wynter, a former Senator, ambassador, and Editor in Chief of Jamaica’s largest and oldest newspaper, the Gleaner.

He threw himself into the life of the University of the West Indies, which was at the forefront of forging a new Caribbean identity and became one of its first chaplains. Islands of the English-speaking Caribbean and the South American country of British Guyana joined a loose federation of ten countries, called the West Indian Federation. The headwinds of a strong, Caribbean-wide movement had, like a Caribbean tropical storm, touched the shores of the ten territories. In the end, it proved too strong a wind, and the federation could not withstand its weighty load.

Parallel to the movement to forge a shared Caribbean identity and single statehood, was the push for autonomy and independence. When Jamaica, by referendum, pulled out of the federation in 1961, Trinidad’s premier, Eric Williams, made the infamous declaration, “One from ten leaves naught,” and promptly withdrew the oil rich island out of the West Indian Federation. The federal government, headed by Grantley Adams of Barbados, immediately collapsed, as two of the major players were now out.

Russell shakes his head in regret and announces it as an opportunity lost. The young intellectuals were deflated. With federation a lost dream, most turned their attention to making an independent Jamaica viable, a status attained on August 6, 1962.

The church in Jamaica also sought to transform into an independent entity. Most of Jamaica’s historical churches at the time had strong links with headquarters in the United States or Europe, and often, were under their direct control. The Jamaica Baptist Union, quite possibly the most independent Jamaican historical church body at the time, still maintained strong links with the Baptist Missionary Society out of Britain, notably through the provision of wardens, lecturers, and tutors at Calabar Theological College.

Much of Christian theology that prevailed had deep roots in the north and had strong distinct features of the West. The struggle for ecclesial independence was as much about theology, ideology and philosophy, as it was about administration and property. Among the most obvious and tangible changes were the theological schools of the various churches.

With the University of the West Indies now granting its own degrees (previously, it was named the University College of the West Indies, with degrees granted by the University of London), the Anglicans, Disciples of Christ, Methodists, Moravians, Presbyterians and others, along with the JBU, sought affiliation of their schools with the UWI. The best solution: form one institution. Thus, in the mid-1960s, all the churches closed their schools and inaugurated the United Theological College of the West Indies, which eventually became the premier Protestant school of theology in the Commonwealth Caribbean, with degrees granted by the UWI.

Russell played a pivotal role in these developments. He, along with another Baptist tutor, the revered British expatriate David Jellyman, and a Canadian consultant, drafted the original documents that led to the formation of the UTCWI. Russell helped to design the campus. The concept, he said, was to foster a family atmosphere. He became one of the first lecturers at the new entity, eventually becoming the college’s first person of African descent to head the school in 1972.

Having trained pastors for much of his adult life, Russell wanted to become one himself. In 1976, Russell left his post as president of UTCWI to become pastor at the historic East Queen Street Baptist Church in downtown Kingston, the oldest Baptist church on the island. It was, by all accounts, a most inauspicious move. Though a veteran of the church, Russell was an inexperienced pastor, and he headed a church steeped in tradition in what had become one of the most volatile areas in Jamaica.

The years 1974 to 1980 were turbulent. The Cold War, having reached Jamaica’s shores, took vicious forms. The two major political parties – the Jamaica Labour Party, founded by Bustamante, and the Peoples National Party, founded by Manley and headed by his son Michael – drew lines in the sand on ideological and territorial grounds. The Michael Manley government espoused democratic socialism and overtly courted close relationships with Cuba, while the opposition JLP, under Edward Seaga, was avowedly pro-USA. Certain communities in Kingston were “JLP areas” while others were “PNP areas,” which the late UWI professor, pollster, and newspaper columnist Carl Stone later dubbed “garrison constituencies.” Each area was defended by political gangs, armed with high powered weapons. The rule of law, when it tried to exert authority, often did so violently. The three-way violence between JLP and PNP gangs, and the police against the gangs, caused the spilling of much blood, creating instability, fear, and a collapsed economy.

Russell suggests that Cuban intelligence officers, KGB operatives from the Soviet Union, and CIA agents from the US, operated in Jamaica. He implies that some of the atrocities committed in Jamaica in the 1970s, had the involvement of one or more of these agencies.

He reported having to rescue young men from certain death, responding to the desperate pleadings of their mothers. In one instance, he assisted a young man who escaped the infamous “Green Bay Massacre,” the alleged execution of suspected gangsters by the military on January 5, 1978, to leave the country.

Russell’s tenure at East Queen Street placed him at the center of power, influence, and violence. As the pastor of a historic church in one of Jamaica’s most respected faith traditions, Russell rubbed shoulders with politicians and political thugs, even as desperate residents and leaders alike called upon him to be a calming influence in the torn and divided communities in downtown Kingston. He tells stories of being called to scenes of shootings, and the only attempt he could take to ensure some measure of personal safety was to make certain he had on his pastor’s collar, making it as visible as possible.

So respected was Russell that the Jamaican government drew on his expertise. He served as a member of the Public Service Commission for eight years, the body that makes appointments and performs regulatory functions for Jamaica’s civil service. He chaired the Jamaica National Heritage Trust, which oversees, protects and promotes Jamaica’s architectural and physical heritage. He served on the Jamaica Cultural Development Commission, which oversees, protects and promotes Jamaica’s cultural heritage in the visual and performing arts and literature. He was named to the Committee for Government Administrative Reform which was tasked with the responsibility to recommend reforms and changes to the government and the civil service. He was part of the National Committee for Curriculum Development in Jamaican primary and secondary schools.

Despite such involvements, what Russell is most known as is as a churchman. For him, the most endearing and enduring of all his involvements and accomplishments was as a pastor, such as the planting of the Edgewater Baptist Church and the founding of the Waterford Baptist Church, both of which spurred Baptist witness in Jamaica’s fastest growing city of Portmore. He was pastor to the rich and the poor, the powerful and the powerless, one of the few genuine links between the two disparate groups in an increasingly polarized society.

Yet, Russell did not confine himself to Jamaica. From 1968 to 1990, he served as a member of the Faith and Order Commission (FOC) of the World Council of Churches, one of the most highly regarded memberships in world Christianity. The first person from the Caribbean to do so, he eventually served in the prestigious position as Vice Moderator of the FOC’s Standing Commission. Baptist World Alliance General Secretary Neville Callam, a fellow Jamaican who succeeded Russell on the FOC in 1990, himself an erudite scholar from out of Harvard, described his 15-year experience on the FOC as “my university.” It is in the FOC that some of the most cutting-edge, rigorous, and exacting theological discourses and scholarship take place.

He became involved with the Baptist World Alliance, serving on that body’s Commission on Baptist Heritage and Identity, and its Academic and Theological Education Workgroup.

Russell did make a physical transition from out of Jamaica and began what can be termed a third phase in his life as a churchman. The first phase was in academia, at Calabar, then at UTCWI. The second phase was that of pastor at the East Queen Street Baptist Church. In 1990 Russell took up the position of professor of historical theology at Eastern Baptist Theological Seminary near Philadelphia in the United States, (since renamed Palmer Theological Seminary). He was also named vice president and dean of chapel at the major Baptist school of theology in the northeast USA.

The church historian, regarded as the foremost in his field in the English-speaking Caribbean, continued his historical and theological interests outside of the classroom, as was the case while in Jamaica. He holds professional status within the American Society of Church History and the American Baptist Historical Society. He has continued his long association with the Society for the Study of Black Religion, the Marcus Garvey Foundation, and with the National Heritage Trust of America.

But, in going to Philadelphia, Horace Russell took his own advice. A seminary or theological college professor, he believes, should remain a pastor. His five years as interim pastor at Saints Memorial Baptist Church in Bryn Mawr near Philadelphia, led to him becoming the congregation’s senior pastor since 1997, a position he holds despite retiring from Eastern seminary in 2002.

He has held lectureships and consultancies with some of the most august academic and church institutions, including Cambridge University in England, Andover-Newton Theological Seminary in Massachusetts, Michigan State University, and the National Council of Churches USA, among dozens of others.

In all this, Russell was a prolific writer, much of it coming from his own groundbreaking work in Caribbean Church History, as well as in theology, mission, and ecumenism, writing half a dozen books and numerous journal articles and book chapters.

Family is, of course, dear to Horace Russell’s heart, married for more than 50 years, and blessed with three children, Elizabeth, Heather, and Jonathan.

One may describe Horace Russell as a renaissance man, a man for all seasons, a man who moves with ease between genres, whose level of competence is as broad as his intellectual reach.

A Caribbean pioneer, among the few remaining from an era that has helped to shape a Caribbean vision and intellectual thought, and who was at the forefront of forging a new Caribbean theology.

Eron Henry is author of Constitutionally Religious: What the Constitutions of 180 Countries Say About Religion and Belief and the novel, Reverend Mother.

Great tribute. In Him there was no dichotomy between the spiritual, the intellectual and koinonia. He lit the candle and himself became the candle for those still searching. And none left behind.