By Eron Henry

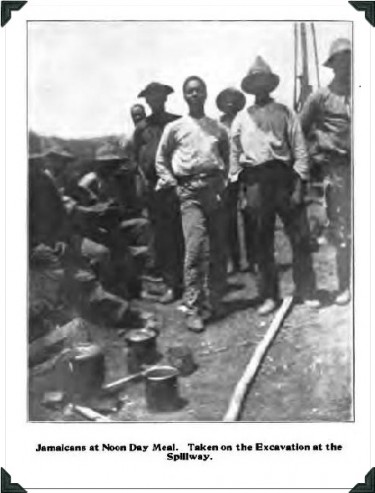

Jamaicans have had a long history with Panama. Tens of thousands of Jamaicans and other Caribbean migrants worked on the construction of the railroad, the Panama Canal as well as on the estates of the United Fruit Company.

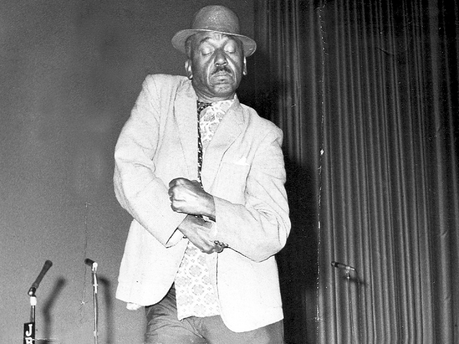

My own father in law lived and worked in Panama prior to returning to Jamaica where he met my mother in law. Several prominent Jamaicans, such as the famed West Indian cricketer George Headley and comedian and actor Ranny “Mas Ran” Williams were born in Panama to Jamaican parents.

The West Indian heritage in Panama, especially in the city of Colón, is evident. Colón is a city and port near the Caribbean Sea, lying near the Atlantic entrance to the Panama Canal. On a visit there a few years ago, the city teemed with descendants of Caribbean immigrants, Jamaicans, Barbadians and others, including our interpreter, who has a very English language first and last name.

Canal construction

A BBC report indicated that “most of the Canal’s workforce during the US construction period in the early 20th century arrived in Panama from the West Indies, on board the steamship Cristobal.” The canal construction was done by French investors from 1881-1894 and was taken over by the Americans after the French experienced construction problems, delays, bankruptcy, and legal troubles.

The Jamaican and other colonial governments were reluctant to have their residents continue to work on the canal. “The Caribbean governments were reluctant to allow recruiting, because at the end of the French period of construction, many of the West Indian labourers had been stranded in Panama, and they had to be repatriated at their governments’ expense,” the BBC reported. Even after Barbados acquiesced, “Jamaica refused to allow any recruiting, and placed a tax of one pound sterling on anyone wishing to work in Panama. This meant that the Jamaican workers in Panama were mostly skilled workers, as only they could afford the tax.”

Eventually, Jamaicans started arriving in greater numbers, but things were not great. The following paragraph from Wikipedia tells part of the story:

In November 1903, the construction of the Panama Canal began. 50,000 workers were imported from Jamaica, Martinique, Barbados and Trinidad. The workers were referred to as Antilleans or derisively as chombos. Antilleans and other black workers were paid less than white workers. Discrimination was rampant. Most supervisors were from the southern US, and implemented a type of southern segregation. The presence of West Indians had other repercussions. Creoles and mestizos who had a social status above blacks were lumped with them. They were deeply offended and engaged in rampant discrimination of all blacks outside the general canal local. This led to great racial tension. Native blacks began to resent the West Indians, who they felt made things worse for them. In 1914, the Panama Canal was completed. 20,000 West Indians remained in the country. They generated a lot of xenophobia. In 1926, Panama passed laws decreasing immigration from the West Indies and later barring non-Spanish speaking blacks from entering the country.

A United States Public Broadcasting Station (PBS) feature noted that immigrants who worked on the canal encountered “harsh terrain, disease, and deplorable living conditions” and that “their pay and quality of life often directly related to their ethnicity.” I heard stories of West Indians, either homeless or mentally ill, roaming the streets of Colón, Cristobal and elsewhere, due, it is believed, to the way they lived and were treated. Many did not return to their homeland because of shame as they had little to show for their time away. Others did not have the means to return. Many thousands had died from infectious diseases, especially malaria and yellow fever.

The same conditions existed during the construction of the railroad several decades earlier. The first set of Jamaicans arrived in the early 1880s, when, “in 1881, French recruiter Charles Gadpaille ran advertisements throughout Jamaica, offering wages much higher than average on the Caribbean island,” said the PBS report.

Deception

The advertising campaign was deceptive, as building the railroad, whose construction began in the 1850’s with immigrant workers from elsewhere such as China, was as treacherous as it was for the canal later:

The campaign showed the “Colón Man,” a Jamaican who had gone to work in Panama, returning to his home country a rich and prosperous man. This ideal caught on quickly in the largely working-class country, and drove a huge migration of Jamaicans to Panama in the latter half of the 19th century. But the promise of riches was an empty one: in reality, West Indians earned $0.10 an hour and the work was treacherous. During the eight-year French excavation period, of the more than 20,000 workers who died, most were West Indians. Strikes proved fruitless, as there were always more men eager to take the jobs. Despite the heavy recruitment of laborers from the West Indies, Colombia, and Cuba, only one in five workers stayed on the job longer than a year.

Large numbers of Jamaicans also traveled to Panama, as well as to other Central American countries, to work on banana plantations of the American-owned United Fruit Company. “From 1910 to 1913 around 20,000 Jamaicans migrated to the Limon province of Costa Rica to work on United Fruit’s banana plantations,” an article by Washington State University’s Taylor Choonhaurai, stated. Large numbers of banana plantation workers from Jamaica went to Panama as well, which neighbors Costa Rica. The same mistreatment and malfeasance that occurred with the Panama railway and canal construction prevailed on the United Fruit Company’s plantations.

The Jamaica-Panama connection remains, but it appears to be tenuous. The Jamaica Baptist Union has been sending missioners to pastor the First Isthmian Baptist Church in Colón over many decades. Horace Russell, perhaps the leading expert on Caribbean church history, wrote a touching biography of Baptist missionary, Terrence Haddon Duncanson, who spent more than 30 years in Panama, from 1913 until his retirement in 1945. He succeeded another Jamaican, Felix Gordon Veitch, who had studied both theology and medicine, but spent only a short time in Panama. After returning to Jamaica, Duncanson became pastor in Linstead, St. Catherine.

While in Panama, Duncanson was a spiritual guide and support for Caribbean immigrants. He was responsible for the planting of a number of churches. Due to his lack of confidence in the Jamaica Baptist Union to continue the work, he handed the care and support of the churches to the Southern Baptist Convention of the United States. That, in part, explained the loss of a part of the Caribbean Christian legacy in the Central American country.

Except for the First Isthmian Baptist Church, the Jamaica-Panama Baptist connection is mostly lost. It would be interesting to learn what other connections remain between both countries, such as relatives on both sides of the Caribbean Sea making contact with each other.

Eron Henry is an ordained minister, public speaker, writer, editor and traveler. He is principal of the communications consultancy, Eron Henry & Associates. His novel, Reverend Mother, is available on Amazon. He can be reached at eronhenry2@gmail.com

Very interesting.Now I know I have relatives who went there.They returned with little. One was able to buy land in deep rural area.I can only remember the large Spanish Jars in his house and a tin pan for storage. He seem to be one for f the better ones.

How does the song relates? 1234 Colo Man a Cum.

Is this song in reference to Colon by any chance?

Apparently it is related to Jamaicans/Caribbean folk working/living in Colon, Panama. I’ve been to Colon where there are many West Indian descendants

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=czQi7S6iMrs

This video supposedly explains your question

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VDY4rFGo3GQ

Yes, a funny song but also a song that describes the violence and discrimination the men received once returning from Panama. 1, 2, 3, 4 lik him belly Pram Pram.

Barbados/Panama

Grandfather Kirton worked at the Cristobal branch of the Canal in Gatun from 1907-1914 when the work was finished. He stayed in Gatun until his death 1942. When I Think of those Wicked Southern Generals and their “Jim Crow” b. s. in Panama… Grandfather did leave a Legacy of children. Now he has great-great-grandchildren all over the U. S. and some in Panama too. Blessings to All! We have Much to be Proud of even if we Never get the recognition for our Ancestors. Tell the story to your children. Save pictures. Much love🌿🌿🌿🌿🌿🌿🌿🌿🌿🌹

I’m currently reading Panama Fever by Matthew Parker and though there are many books out there reading this book I can understand what our relatives endured in the construction of the Canal. Division was the intention of the contractors. Gold Standard for whites and other people that looked European. Silver Standard for all other nationalities that weren’t white. The sad part is that the workers from the Antilles worked hard and were the backbone to the completion of the canal. The Black African Americans were also sent to The canal to try and make some type of division between the men from the Antilles but were sent back because they complained about their treatment. Imagine leaving the Caribbean to go to Panama, fighting the Colombians, whites, living in shacks, insect, rats and other animal born viruses and attacks. Not to forget the poor nutrition. Then to return home and being robbed or scammed of what money was saved. Our ancestors that endured this treatment overcame(a lot didn’t) and helped their children advance. I thank them for that. So much had occurred, I didn’t even know that Nicaragua was another area for a canal the Americans wanted instead of Columbia(before Panama ceded with the help of the Americans).