Before bustling Kingston came to be, it was merely a small village. Evidence suggests that there were houses in the area, but it wasn’t until 1673 that the area was officially named Kingston. On a 1689 map in “The English Pilot,” the area where Kingston now stands was labeled “Liguanea,” showing seven small houses and two larger ones. An earlier map from 1684 labeled the area as “Beeston,” reflecting the common practice of identifying places by the names of their owners rather than their actual names.

Kingston’s transformation began in earnest after the devastating earthquake of 1692, which destroyed much of Port Royal. Many merchants and residents relocated to Kingston, seeking a new place to live and conduct business. This influx of people and commerce led to Kingston being officially established as a parish in 1693 through Act 32 passed by the Assembly.

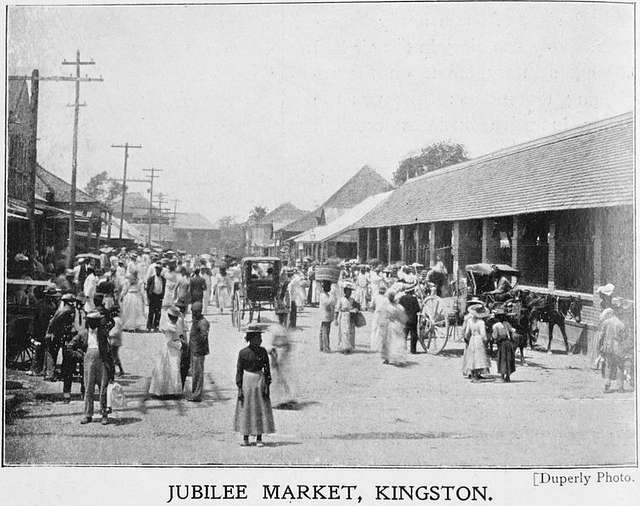

By the end of the 17th century, Kingston had grown significantly, with a population exceeding a thousand people and the establishment of new businesses. The first public market opened in 1703, marking the beginning of Kingston’s development into a commercial hub.

By 1716, Kingston had become the most important town in Jamaica. Its strategic location and growing infrastructure attracted more residents and businesses. However, the town faced challenges, including a significant fire in 1753 that necessitated extensive rebuilding.

The opening of the Port Royal Maritime Canal in 1765 further boosted Kingston’s growth by facilitating easier access for ships into the harbor, thereby increasing trade and commerce. In 1776, Richard Price brought a newspaper press to Kingston, establishing it as a center for printing and earning it the nickname “The Printer’s Mecca.”

19th Century Kingston

Kingston experienced significant growth during the 19th century, becoming the island’s commercial hub and eventually its capital. The city’s population surged, new suburbs emerged, and infrastructure improved, but devastating fires and social unrest also marked this era.

Kingston’s population grew rapidly in the 18th and 19th centuries, rising from 5,000 in 1700 to 35,000 in 1828. The abolition of slavery in 1838 further intensified this growth, with the population reaching 38,566 in 1881 and 48,504 in 1891. This growth was driven by the city’s expanding economy and rural depopulation. New suburban zones, including Rae Town, were added to accommodate the growing population. Established in 1810, Rae Town became a residential area for wealthy French refugees from Haiti and English and Scottish merchants. Kingston’s expansion led to changes in the parish boundaries as communities spilled over into neighboring St. Andrew.

Kingston received its first public water supply from the Hope River in 1842. The railway line to Spanish Town opened in 1845, marking a milestone in transportation and trade. This was the second railway line established in a British colony, after Canada. A coaling station was established near East Street around the mid-19th century, facilitating steamer traffic.

Kingston’s economic growth attracted immigrants, leading to ethnic segmentation of urban space. White citizens, along with Syrians and Jews considered “near-Whites,” occupied the highest-paying jobs and resided in segregated uptown districts like Barbican and Mona Heights. The influx of freed slaves after 1838 created social and economic challenges as the city adapted to a changing labor force.

Kingston suffered several devastating fires in the 19th century, including major ones in 1843 and 1862. A catastrophic fire in 1843 destroyed much of the city, leading to significant property damage. The House of Assembly voted to provide relief to the victims. Despite these setbacks, Kingston’s residents rebuilt and adapted.

In 1866, following the 1865 Morant Bay Rebellion whose aftermath led to significant changes, Kingston’s corporate status was abolished, and an appointed municipal board assumed authority. Kingston finally achieved its long-standing goal of becoming Jamaica’s capital in 1872. Governor Sir John Grant recognized Kingston’s economic and strategic importance and oversaw the transfer of the capital from Spanish Town. This move was a culmination of efforts by Kingston merchants and solidified the city’s preeminence.

Kingston was home to various architectural landmarks, including churches and theaters, reflecting its growing cultural aspirations. The city’s population was diverse, encompassing whites, blacks, Jews, and others, each contributing to its unique character. H.G. DeLisser, writing in the early 20th century, described Kingston as a “space of ambivalence,” reflecting its complex social and cultural dynamics.

By the end of the 19th century, Kingston had evolved into a vibrant but disaster-prone city, shaping its character and setting the stage for its development in the 20th century.

20th Century Kingston

Kingston entered the 20th century as a city marked by both progress and vulnerability. A powerful earthquake struck Kingston on January 14, 1907, causing extensive damage and loss of life. The earthquake, measuring 6.2 on the moment magnitude scale, toppled buildings and shattered infrastructure. A subsequent fire, fueled by damaged gas pipes, further devastated the city, particularly the commercial district. This event marked a turning point in Kingston’s history, leaving a lasting impact on the city’s development. However, the city continued to grow, with its economy diversifying, infrastructure expanding, and a vibrant cultural scene emerging.

By 1913, Kingston had improved in appearance. The journalist and writer H.G. DeLisser noted that King Street, with its use of cement as a building material, was the “finest in all the West Indies.” DeLisser described King Street as “iconic of Kingston” and a symbol of its modernity. However, he also highlighted the “ambivalence” of Kingston as a colonial city, striving for modernity while grappling with the realities of tropical climate, race, and socio-economic inequalities.

The demand for labor in Kingston’s growing economy and the search for a better life drove migration from rural areas. The return of Jamaican laborers from Latin America in the 1930s contributed to the urbanization of Kingston. US and UK anti-immigration measures in the 1950s and 1960s further concentrated migration to Kingston. The population of Kingston increased by 86% between 1943 and 1960, reaching 379,600, a quarter of Jamaica’s total population.

Jamaica’s journey towards independence gained momentum in the 20th century. Labor unrests in 1938 were pivotal in the dawning of a new era, including the formation of labor unions and political parties. In 1944, a new constitution granted universal adult suffrage, extending voting rights to all citizens over 21. This marked a significant step towards greater political participation and representation. The two-party political system emerged, with the People’s National Party (PNP) and the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP) becoming dominant forces. Jamaica achieved full independence from Britain on August 6, 1962. This historic event marked a new era for Kingston, as it became the capital of an independent nation.

Kingston’s economy diversified beyond its traditional focus on trade and commerce. Manufacturing and industrial activities expanded in the mid-20th century. New industries emerged, including tobacco processing, leather goods, mineral water production, and brewing. The establishment of industrial zones, such as the one along Marcus Garvey Drive, fostered economic growth and employment opportunities. Kingston’s port facilities were modernized with the construction of Newport West in the 1960s, enhancing its capacity to handle cargo and facilitate trade.

Tourism emerged as a significant sector in Kingston’s economy. The city’s natural beauty, historical landmarks, and cultural attractions drew visitors from around the world. The Myrtle Bank Hotel, known for its grandeur and luxurious accommodations, played a pivotal role in promoting tourism in Kingston. However, the hotel was destroyed by fire in 1966, marking a loss for the city’s tourism industry. The redevelopment of the Kingston waterfront in the late 20th century aimed to revitalize the area and attract investment, including in tourism.

Despite economic progress, social challenges persisted in Kingston throughout the 20th century. Poverty, overcrowding, and inadequate housing conditions remained pressing issues, particularly in areas like West Kingston. Slums and squatter settlements developed, highlighting the disparities in living standards between different segments of the population.

Kingston’s cultural scene flourished in the 20th century, with music, theater, and the arts playing vital roles in shaping the city’s identity. Western Kingston, particularly Trench Town, became a hub for Jamaican popular music and culture, with genres like rocksteady, reggae, and the Rastafari faith emerging from these communities. The Alpha Boys’ School in Eastern Kingston also played a significant role in nurturing musical talent, producing renowned musicians who contributed to Jamaica’s musical heritage.

21st Century Kingston

In the early 2000s, Kingston focused on urban renewal and modernization. Emancipation Park opened in 2002, providing a green space for recreation and cultural events. The park quickly became a beloved landmark, and a favorite hangout venue for residents and visitors.

The 2010s were marked by significant social and political events. The 2010 Kingston unrest, a period of intense conflict and violence, highlighted ongoing issues of crime and social inequality.

Kingston’s population continued to grow, reaching approximately 937,700 by 2011. This growth brought the need for improved infrastructure and services. Efforts to address these needs included the redevelopment of the Kingston waterfront, aimed at revitalizing the area and attracting investment.

Culturally, Kingston maintained its status as a global music capital. The city’s rich musical heritage was recognized in 2015 when it was designated a UNESCO Creative City of Music. This acknowledgment celebrated Kingston’s ongoing contribution to the global music scene, particularly through reggae and dancehall.