Jamaica led the way in the development of Caribbean tourism. Blessed with lush forests, breathtaking mountains, indigenous species of birds, insects and plants, and beautiful white sand beaches, Jamaica, from very early, became a magnet for travelers.

Sibbald David Scott, writing in 1875 on his trip to Jamaica, described what he saw upon approaching Kingston Harbor while on the ship’s deck. “The aspect of the island is beautiful—almost everything looks beautiful under a powerful sunlight…. On looking upwards there are such hills, or rather mountains, clothed to their summits in luxuriant verdure.”

In the foothills of the Blue Mountains, just below Gordon Town, Scott said “nature was in full luxuriance here: so rich a prospect my eyes had never feasted on before.” As they traveled on, “the air feels purer and cooler as we ascend.” The treacherous but spellbinding journey through small, winding paths and close to steep precipices had him declaring, “It is in truth a garden of Eden run wild.”

Edith Blake, in her article, “The Highlands of Jamaica” for the North American Review in 1892, opened her account by declaring, “What most surprised me after a residence in Jamaica long enough to enable me to form an opinion of the climate all the year round, was its comparative coolness.” Speaking of the higher elevations, she said, “The climate of these uplands is perfect, resembling the most lovely English summer weather, with a fresh, exhilarating feeling in the air that recalls Switzerland and the Alps.”

Alfred Leader, who published Through Jamaica with a Kodak in 1907, echoed Blake’s sentiments. He called Bog Walk “a little Switzerland,” described it as “entrancing,” and declared “it the most attractive place in the Island, and a photographer’s paradise.” Of the famous Bog Walk Gorge, he said, “the river enters a magnificent gorge—its massive fern-decked rock walls rising on the right almost perpendicularly about nine hundred feet, the water rushing along the rocky bed below.”

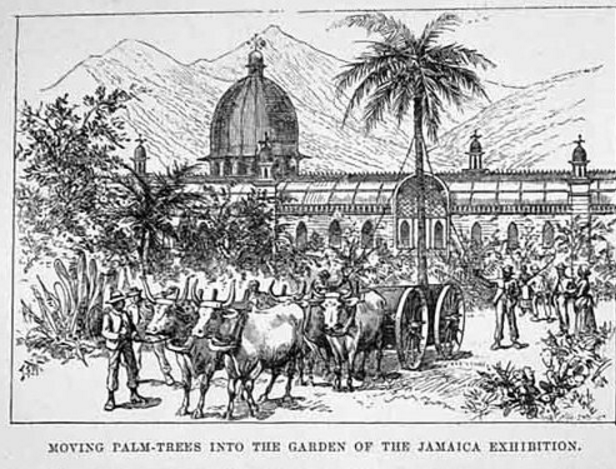

Jamaica International Exhibition

The Jamaica International Exhibition from January 27 to May 2 in 1891, was an important contributor to Jamaica becoming a tourism destination. Jamaica’s governor, Henry Blake, said the exhibition would be “an event of very great importance for the West Indies generally, and one that must have a singular interest for the United States, with its many millions of colored citizens.” England’s Prince of Wales attended the opening.

Conceived in 1889, the exhibition was planned in part to mark the 50th anniversary of the abolition of slavery, though that occurred in 1838; and to increase and improve the marketability of Jamaica’s products.

Governor Blake said the original intention was to hold a local exhibition in Kingston, Jamaica’s capital, and then to make it part of the Colonial Exhibit in London in May 1891. The Jamaican support was so great however, and the enthusiasm level so high, that the Jamaican event itself became an international exhibition.

Significantly, while the government gave its backing, it offered no guarantees. There was no paid staff. The work was done entirely by volunteers. “Architects and engineers came forward, designed the buildings free of charge, and undertook to carry out their erection,” Governor Blake said. “Everybody with technical knowledge on any subject freely offered his services to the committee.”

Support came from local donors with three providing guarantees of £15,000, or about £1.74 million in today’s money. In all, £30,000 worth of guarantees were received or £3.48 million in current money. Much of the PR work was done through the churches and schools to get the involvement of small farmers and rural folk.

Parts of the island underwent an overhaul. Bridges were built in St. Thomas and Portland. The Public Works Department took charge of and upgraded various roads. The Railway Company expanded its fleet and tracks. Hotel construction was encouraged through the Jamaica Hotels Law, passed in 1890. According to the Jamaica Tourist Board:

The Government offered to guarantee the capital at 3 percent interest, for all approved hotel construction and maintenance of approved hotels and also that all building materials and furniture required for such hotels be admitted into the island duty free. As a result several hotels were built not only for the Exhibition, but for those who, having been introduced to Jamaica, would come again and bring others.

Among the hotels built because of government incentives was the majestic Myrtle Bank Hotel, the Queens, Hotel Rio Cobre, the Moneague Hotel, the Titchfield Hotel and the Mandeville Hotel.

The Exhibit venue itself was on what is now the Wolmer’s Girls School.

Different forms of agricultural products, farm animals such as horses, cattle, sheep, goats and bees, and items made by artisans, silversmiths, craftsmen and craftswomen, were on display. “There is nothing which you grow or make which will not find a place in the exhibition,” the governor said in his invitation sent around the island. Some 90,000 copies of his message were distributed island wide.

More than 300,000 persons attended the exhibition, with between 13,000 and 14,000 present at the closing session that ended with fireworks. The Jamaica International Exhibition brought a boom to the Jamaican economy. The financial year, March 31, 1891, ended with a handsome surplus of £172,000.

Government incentives

The next phase of Jamaican and Caribbean tourism development occurred in the 1920s when the industry became more formally organized. The government established the Tourist Trade Development Board in 1922, which was merged with the Tourist Trade Development Board in 1926. Government spent annual sums to promote the country as a tourism destination, collaborating with hotels and shipping companies. This led to a sharp rise in the number of rooms available, and Montego Bay on the northwest coast of the island became a favored destination.

The 1930s saw further growth. A travel tax was imposed to help finance promotion. Political problems in nearby Cuba led visitors to choose Jamaica as an alternative vacation destination. Airlines such as Pan Am expanded and improved international air travel, which increased even further after the end of World War II.

With tourism now big business, the Jamaica Tourist Board (JTB) was formed in 1955, displacing the Tourist Trade Development Board. JTB offices were opened in major cities such as New York, Miami, Chicago and London. The Jamaica Hotels Aids Law of 1963 allowed duty free importation of materials for the construction of new and the expansion of existing hotels.

Some wealthy and well-known personalities, such as the Hollywood actor Errol Flynn and British author, Ian Fleming, creator of the James Bond franchise, bought property in Jamaica and lived at least part time on the island. Flynn, who owned the Titchfield Hotel in Portland in eastern Jamaica, helped to develop the tourism industry in that part of the island. It was he who popularized river rafting on the Rio Grande as an attraction for visitors after witnessing banana farmers transporting their products on bamboo rafts from their farms down river to the port.

Today, tourism is Jamaica’s largest single business. More than 50 percent of the country’s income is earned from tourism, which employs some 25 percent of workers. Massive hotels now grace the north coast from Negril in the west to Ocho Rios in the east. Other large properties are slated for development, with the largest yet, Harmony Cove in Trelawny to be built on 1,400 acres, still on the drawing board. A mega resort and casino, Harmony Cove is projected to have as many as 5,000 rooms.

It could be argued that though Jamaica gets some three million overseas visitors per year, more than the country’s population, the majority do not get to see the most beautiful parts. Restricting their stays to the coasts where they laze on the beaches, they do not see or experience what so enthralled Sibbald David Scott, Edith Blake, Alfred Leader and others in the early days: the lush forests, the breathtaking mountains, meandering rivers and invigorating mineral springs. Perhaps that is just as well. Massive crowds at such venues and locations may just water down the experience.

Pretty

Another good one Rev. Keep em coming. Went paragliding in Negril last year for the first time. I have never seen such beauty from above in my entire life.

Can be a local’s paradise as well (ha, that happens to be the tagline of my site) 🙂