Jamaicans become Brazilians during World Cup football. The love affair goes back to the halcyon days of Brazilian soccer in the late 1950s into the early 1980s. Edson Arantes do Nascimento – Pele – set Jamaican hearts and imaginations on fire with his speed and brilliance on the football pitch. The supporting cast of Rivelino, Jairzinho, Tostão and Gérson were magical. Experts labeled the 1970 Brazilian squad as the greatest ever assembled to play on one side.

The 1982 Brazilian team, regarded as the greatest never to have won a World Cup tournament, broke every Jamaican heart. Some Jamaicans never got over nor ever forgave Paulo Rossi of Italy for sinking deep daggers into every Brazilian lover’s heart with his hattrick of goals in the 1982 second round match between the two. Up to that point, Italy was not very impressive – drawing all three of their first-round games and scraping through to the second round– while Brazil was sublime up until then.

That Brazilian team was studded with star power, except for goalkeeper Peres and forward, Serginho, who committed unforgivable errors. The Brazilian names rolled off the tongue – Socrates, Falcão, Zico, Eder, Junior and Leandro.

Though subsequent teams have not been as flashy or skillful, except for occasionally brilliant players such as Ronaldo and Ronaldinho, Jamaica, like a longsuffering lover, keeps returning to the Brazilian fold every four years. Hence, the World Cup tournament currently underway in Russia has many Jamaican hearts palpitating whenever Brazil takes the field.

Jamaican love for Brazilian soccer was sealed when Brazilian coach René Simões led Jamaica into the 1998 World Cup tournament in France, the first English speaking Caribbean nation to do so. Having such deep affinity for Brazilian football, one wonders if the Jamaican fascination ends there.

Brazil and reggae

As it turns out, some Brazilians are fascinated with Jamaica. Whereas Jamaicans are enamored by Brazilian soccer, Brazilians are enraptured by Jamaican music. Northeastern Brazil, especially the states of Bahia and Maranhão, have long been strongly influenced by Jamaica. In these and other parts, there is great admiration for Jamaican culture, especially reggae and the Rastafarian movement.

There are suggestions reggae music in Brazil took root at parties in the 1970s before migrating to radio. André Cabette Fábio says, “Caribbean rhythms arrived in the capital of Maranhão through radio waves and records. Over time, reggae won the local audience.” Journalist and anthropologist Karla Freire recounts that “several people in their 50s and 60s say they listened to Jamaican music on the radio even when they did not even know what reggae was.”

There are speculations as to why reggae became popular in northeast Brazil. “Some researchers argue that the style has a similar beat to local folk rhythms, such as bumba-meu-boi or creole drummer,” Fábio says.

Kavin Dayanandan Paulraj’s 2013 PhD dissertation explores ties and links between both nations:

Residents of São Luís like to say that reggae music reached their island city in Maranhão state in northeast Brazil “through the back door,” into makeshift venues deep in urban slums. In time, audiences in São Luís cultivated a cosmopolitan music scene and an innovative cultural industry that earned their city the title of Jamaica Brasileira, or the Brazilian Jamaica…. [T]his dissertation explores how and why reggae developed local roots in São Luís and its subsequent role in local socio-economic and political developments.

What Paulraj says of São Luís could be said of Salvador, capital of Bahia.

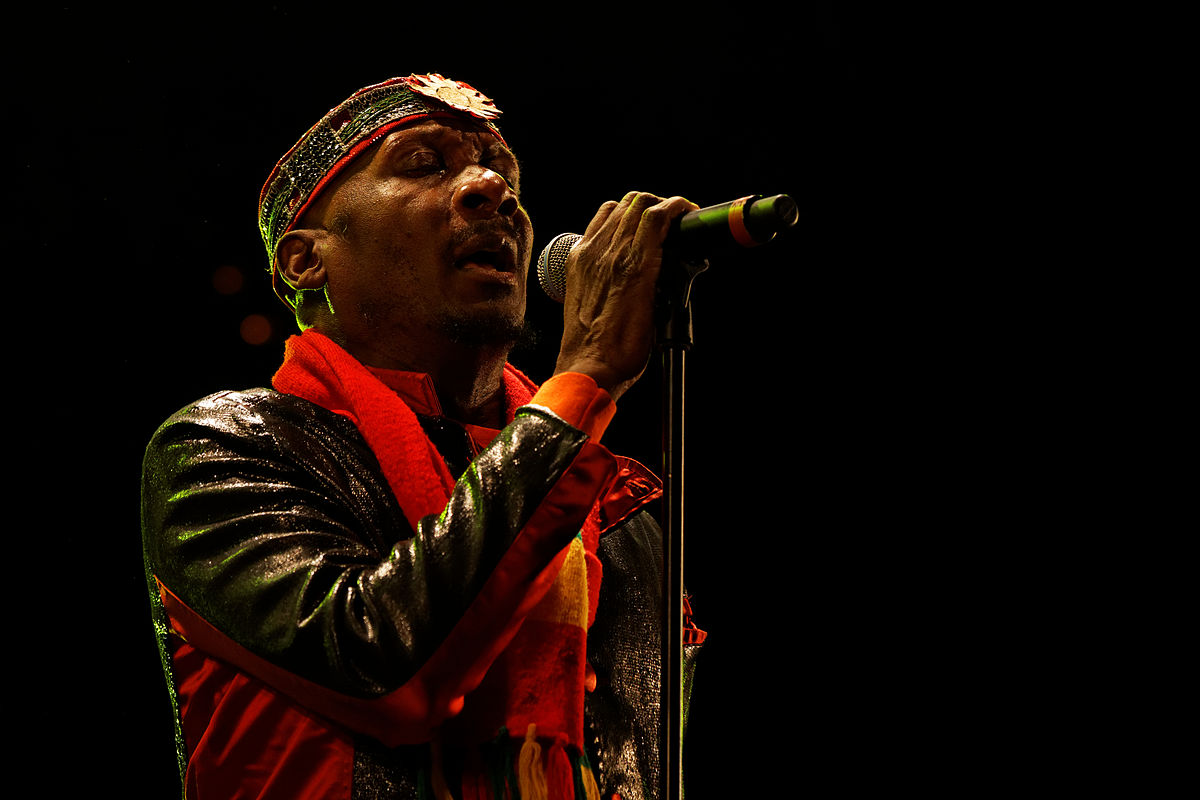

Jimmy Cliff, who almost became what Bob Marley has become, except for one cruel twist of fate, is highly popular in Brazil. “Jamaican songs, melodies, and rhythms arrived in São Luís mostly thanks to international pop, largely via the Jamaican singer Jimmy Cliff,” says Paulraj. Cliff had consequential political influence:

Soon after it entered the public social consciousness of São Luís, the reggae scene was thrust into the forefront of Maranhão political world in the gubernatorial race of 1990. It started controversially, with a moment of patronage – a performance by Jamaican legend Jimmy Cliff to celebrate the victory of governor-elect Edison Lobão. Soon, reggae radio personality Ademar Danilo was elected to city council with votes from reggae audiences and black movement activists in 1992…. Reggae’s powerful electoral potential returned spectacularly in the 2000s with the ascent of the premier reggae businessman José Eleonildo Soares (also known as Pinto da Itamaraty) to the federal congress in 2006.

Bob Marley visited Brazil in 1980 in preparation for a world tour. While there, he played football and met significant figures in Brazil’s reggae scene. Marley experimented with samba music. University of the West Indies Professor Carolyn Cooper claims:

In private conversation with me, legendary Jamaican footballer Allan ‘Skill’ Cole, Marley’s long-time friend and producer of the song “Lick Samba,” disclosed that it was his own involvement with football in Brazil that sparked Bob Marley’s experimentation with samba. That football connection is a whole other story of cultural synergies.

Multi-Grammy winning singer and performer, Ziggy Marley, Bob’s son, toured Brazil several times, including in 2011 and 2013. He points to similarities between Jamaicans and Brazilians. “The love of music is the great similarity between the countries. There is no difference between the two places. The people are the same.”

Historical similarities

On the face of it, Jamaica and Brazil could never be more different. One is huge in size and population, the other relatively small. One is an island, the other dominates a continent. They have different colonial and political histories. Language and culture are quite different. Yet Amanda Moore finds connections that run deep. In her 2005 paper for the Syracuse University Honors Program Capstone, she unearths similarities between 18th century and 19th century maroon communities in Jamaica and Brazil, as well as Mexico:

Brazilian, Jamaican and Mexican mocambos (communities mainly of runaway slaves) all established systems of integrating and acculturating new entrees into their societies. All mocambo inhabitants were particularly suspicious of new members. The existence of mocambos depended upon their ability to remain inaccessible and hidden. Therefore, secrecy and unwavering allegiance to Maroons were necessary to maintain the lifestyle and success of all mocambos and quilombos. Each society established its own ways to evaluate newcomers and integrate approved maroons.

In addition:

The majority of Brazilian, Jamaican and Mexican mocambos were founded in two locations: within close proximity of, but inaccessible to 35 colonial societies, or deeply secluded within the land yet uncharted by Europeans.

She cites other similarities. “Maroons of Brazil, Jamaica and Mexico produced provisions within their mocambos…. Maroon women of Brazil, Jamaica and Mexico were highly valued, performed similar tasks and had important roles as spiritual and religious leaders.”

Maroons in all three countries entered a treaty with colonial governments to recapture or return the enslaved who ran away. “The Brazilian and Jamaican colonial governments enlisted other enslaved Africans and Freedmen as into Black militia troops called Black Shots,” Moore asserts.

Formal ties

There are formal ties between Jamaica and Brazil. Both established diplomatic relationship in October 1962, shortly after Jamaica’s independence. Jamaica opened its embassy in Brazil in 2015 after establishing a diplomatic mission in 2012. Brazil has its embassy in Kingston, Jamaica’s capital.

The Jamaica-Brazil Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Tourism, promotes “the common interests of members developing and maintaining commercial, cultural and tourism activities, between Brazil and Jamaica.”

Beginning in 2015, Jamaicans could enter Brazil without need for a visa. Jamaican Ambassador Alison Stone Roofe said then, “Jamaicans tend to travel to Brazil for targeted, specific reasons, for example, visiting friends and relatives, and cultural reasons due to the influence of reggae music and the affinity with the Afro Brazilian population.”

Eron Henry is author of Reverend Mother, a novel. Ole Time Sumting blog was recognized with an Award of Merit by the Religion Communicators Council in April 2018