It is believed many Jamaican songs had oblique meanings and hidden references that only those in the know were aware of. These songs did not indulge in double entendre to the extent Caribbean calypso or soca did. They were sly but were not intended to be naughty, not like Mighty Sparrow’s Salt Fish and similar songs. Jamaican rude songs tend to be obviously naughty, though a few were double entendre, such as Fab Five’s Shaving Cream and Lt. Stitchie’s Wear Yuh Size.

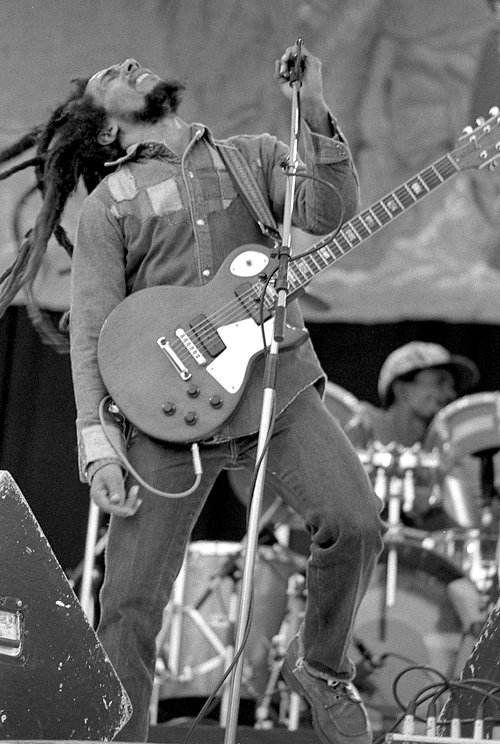

Many of Bob Marley’s songs are believed to have hidden meanings – I Shot the Sheriff, Small Axe, No Woman No Cry, and Who the Cap Fit – among others. The most obvious of Marley’s songs were Ambush in the Night and Coming in From the Cold. The first a reference to an assassination attempt on his life on December 3, 1976. The latter when he returned to Jamaica from self-imposed exile several years following the attack.

Some songs stemmed from feuds between artistes. Toots Hibbert and Justin Hinds, for instance, were said to have had a long running standoff against each other. Hinds threw the first salvo with The Higher the Monkey Climb:

I’m not tracing nor complaining on those goings

He that exalteth himself shall be abased

Grief always comes to those who love to brag the most

Meekly wait and murmur not

You’d better hold on to what you have got

The higher the monkey climbs, is the more he exposes

Hibbert’s retort, Monkey Man, was one of the most biting, a very unkind reference to the alleged profession and practices of Hinds’ father:

I’ve seen no sign of you, I’ve only heard that you huggin’ up the big monkey man…

Is not lie, is not lie, them a tell me, you huggin’ up the big monkey man…

Now I know that, now I understand, you turnin’ a monkey on me

Those in Mount Rosser and surrounding areas in the parishes of St. Catherine and St. Ann would know what it was all about. (We heard stories as children growing up in St. Ann. Some adults would whisper their disgust to each other).

I Shot the Sheriff fit the bill of artistes settling scores, but the primary purpose of this song was possibly to set the record straight and explain what happened. Released in the wake of the acrimonious breakup of the original Wailers, it is believed the Sheriff was Peter Tosh with the Deputy being Bunny Wailer. In other words, Marley and Tosh were the major protagonists, with Bunny Wailer playing only a minor role, in the breakup.

Personal and social upheaval played a part in Jamaican songs. Toots Hibbert, for instance, memorialized his arrest for drug (ganja) possession with 54-46. Marley tried to calm the outbreak of violence among Kingston inner city youth with the Wailers ska hit, Simmer Down. These were early intimations of a social malady in the 1960s that would only get worse in the 1970s going forward:

Simmer down, you lickin’ too hot, so

Simmer down, soon you’ll get dropped, so

Simmer down, can you hear what I say

Desmond Dekker’s 007 (Shanty Town) referenced chaotic inner city life transforming itself into criminality:

At ocean eleven

And now rudeboys a go wail

‘Cause them out of jail

Rudeboys cannot fail

‘Cause them must get bail

Oh, dem a loot, dem a shoot, dem a wail

A shanty town

Dem a loot, dem a shoot, dem a wail

A shanty town

Dem rudeboys get a probation

A shanty town

And rudeboy a bomb up the town

A shanty town

Leroy Smart’s Ballistic Affair got a lot of push, with hopes of stemming the violence, after things got out of hand in 1970s inner city Kingston and St. Andrew.

Throw ‘way your gun

Throw ‘way your knife

Let us all unite

Everyone is living in fear

Just through this ballistic affair

Some songs referenced more truth than the listening public realized. Cottage in Negril spoke of Tyrone Taylor’s struggles and inner demons that, possibly, contributed to his untimely and tragic passing. Some believe Night Nurse by Gregory Isaacs was about a personal fight he never won:

Tell her try your best just to make it quick

Whom attend to the sick

‘Cause there must be something she can do

This heart is broken in two

Tell her it’s a case of emergency

There’s a patient by the name of Gregory

Night nurse

Only you alone can quench this yah thirst

My night nurse, oh gosh

Oh the pain it’s getting worse

I don’t wanna see no doc

I need attendance from my nurse around the clock

‘Cause there’s no prescription for me

She’s the one, the only remedy

Early Jamaican songs

The tradition of Jamaican songs going sideward with implicit references did not begin with ska and reggae. Byron Johnson asserts in his 2010 PhD dissertation that folk songs of the slave era and afterwards were used for “communication, entertainment, and worship.” They were useful “as a mode of communication between slaves and their masters, as well as among the slaves themselves.”

These songs provided an outlet. “An innocent sounding song could announce a prohibited meeting which had to be a closely guarded secret,” wrote Olive Lewin in Rock it Come Over. “Music became an important means of expression and communication. Ideas, news and comments that could not be spoken, could be sung.”

Some folk songs were used to “throw words” at slave owners and others. “A song about birds…had nothing to do with birds,” Lewin said. “[R]eferences to John Crow (a scavenger), parrot (chatterbox), woodpecker, blackbird (the farmer’s foe, living by robbing his cultivation) related to unpopular individuals and needed no further explanation.”

The Banana Boat Song, traditionally dating to the the early 20th century and immortalized by Harry Belafonte in 1956 as Day O, indicated a shift to the dominance of Jamaican banana export over that of sugar. Writing in the New Yorker, Amanda Petrusich speculates that the song was “likely concocted spontaneously by overnight dockworkers cramming bunches of bananas onto ships, hot-footing it away from loose spiders, and fantasizing about rum.”

1930s music was exemplified by the “blues” of Slim and Sam, the most popular group of the era. Pamela and Martin Mordecai both note in Culture and Customs of Jamaica:

Some of their songs were based on traditional tunes with which their audience would have been very familiar and to which Slim and Sam wrote new words about everyday events around them – court cases, society scandals, political events – with idiomatic expressions and double entendres that their audience would recognize.

There is indeed much to Jamaican songs. Ibo Changa says of Marley’s music in the Encyclopedia of Black Studies:

Marley’s Roots and Conscious Reggae is made up of sweet songs of black love, protest songs of black rebellion, powerful songs of black liberation, and sorrowful songs of black redemption, which use African Jamaican double entendre, metaphors, proverbs, parables, utterances, call-and-response, and biblical references, to touch the spiritual and cultural ethos of people of African descent and others who can feel what is in the music.

Eron Henry is author of Reverend Mother, a novel. Ole Time Sumting blog was recognized with an Award of Merit by the Religion Communicators Council in April 2018

An illuminating and refreshing post. Now I have to go back and listen to Lt. Stitchie’s Wear Yuh Size. Hehe.