Though Islam has never taken deep roots in Jamaica, it has had a long-standing presence on the island.

With thousands of enslaved persons from Africa brought to Jamaica for more than three centuries, some, perhaps many, must have been Muslims. Islam had had an early presence in West Africa, from where most enslaved persons in the Americas originated.

Estimates are that as many as 16 percent of indentured workers from India who came to Jamaica after full emancipation in 1838 were Muslims. It is possible too that, while most Lebanese who came here in the latter half of the 19th century were Christians, some of these Arabs may have been Muslims.

While the evidence is not conclusive, there are traces suggesting Islamic presence in Jamaica from the time of the Spanish occupation of the island, which began in 1494 and ended in 1655 when the British took the island by force from Spanish control.

Jamaica’s official website for visitors states confidently:

Islam has been practiced in Jamaica since the 1500s, when African slaves brought the religion during the African Slave Trade. The religion was practiced more widely however after the abolition of slavery in 1834 with the arrival of Indian laborers.

In 2000, Sultana Afroz, a Muslim from Bangladesh and a lecturer at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica, implied that at least some Jamaican maroons were Muslims. “‘As-Salamu-’alaikum,’ the Islamic greeting in Arabic, meaning ‘peace be upon you,’ continued to be the official greeting among the Maroon Council members in Mooretown, Portland, Jamaica.”

In 2001, Afroz wrote that “[c]ontemporaneous to the autonomous Muslim Maroon ummah, hundreds of thousands of Mu’minun (the Believers of the Islamic faith) of African descent worked as slaves on the plantations in Jamaica.”

She made the remarkable claim that Sam Sharpe was Muslim and the Rebellion he led was Islamic jihad:

Jihad became the religious and political ideology of these crypto-Muslims, who became members of the various denominational nonconformist churches since being sprinkled with the water by the rectors of the parishes. Despite the experience of the most cruel servitude and the likelihood of a swift and ruthless suppression of the rebellion, the spiritually inspired Mu’minun collectively responded to the call for an island-wide jihad in 1832. Commonly known as the Baptist Rebellion, the Jihad of 1832 wrought havoc of irreparable dimension to the plantation system and hastened the Emancipation Act of 1833.

She said, “the dhikir, ‘Allahu Akbar,’ declaring the Greatness of Allah, still throbbed in the hearts of many of the former Muslim slaves when the Indian indentured Muslims first landed in Jamaica in 1845.” She made reference to “the many freed African Muslim slaves in the midst of great social, economic and political uncertainties following emancipation.”

Afroz further asserted that “with the arrival of the indentured Muslims from India, the peaceful revival of Islam in Jamaica began.”

Gordon Mullings said Afroz’s claims rest on a “shaky historical and cultural foundation.” Furthermore:

[T]he overwhelming historical and anthropological evidence is that our “crypto-Muslim” African ancestors were in fact predominantly and very actively animistic, and that Islam first gained a significant institutionalized presence in the region with the settlement of Indian indentured laborers in the mid-nineteenth century. As for the concept that the Maroons were Moorish/Islamic to the point of constituting an Islamic community under Islamic law (i.e. an ummah), one should start by considering the fact that they have been famous, from Spanish times, for Jerk Pork — a major Islamic no-no.

Maureen Warner-Lewis, a UWI professor, said Afroz was engaging in a revisionism of Jamaica’s history. Her assertions were bedeviled by “inaccuracies of data and faults of argumentation.” In addition:

There are glaring disjunctures between the sweeping claims advanced and the paucity of the evidence proffered, while logic is defied by extravagance of assertion, leaps in assumptions, and glib transitions from probability to dogmatism.

She said Afroz employed “doubtful logic to the production of questionable historiography.” Among other things, she inflates “the number of enslaved Muslims in Jamaica” and she “distorts comments made by some nineteenth-century commentators.”

Warner-Lewis did not dispute early or longstanding Muslim presence on the island. Rather, she accused Afroz of overstating the case and for misreading history.

Some of these enslaved Muslims were literate. Warner-Lewis declared:

The religious ideas of these Muslims as well as the writing skills in Arabic which several of them possessed had in fact caught the attention of European planters, among them Jamaican-based Bryan Edwards (1819). In fact their numeracy and writing skills allowed them to secure jobs as storekeepers and tally clerks on estates.

Furthermore, “Magistrate R. R. Madden of Jamaica alerted anti-slavery and Africa colonisation interests in London to the Arabic autobiography (1830s) of Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, otherwise called Edward Donlan in Jamaica.”

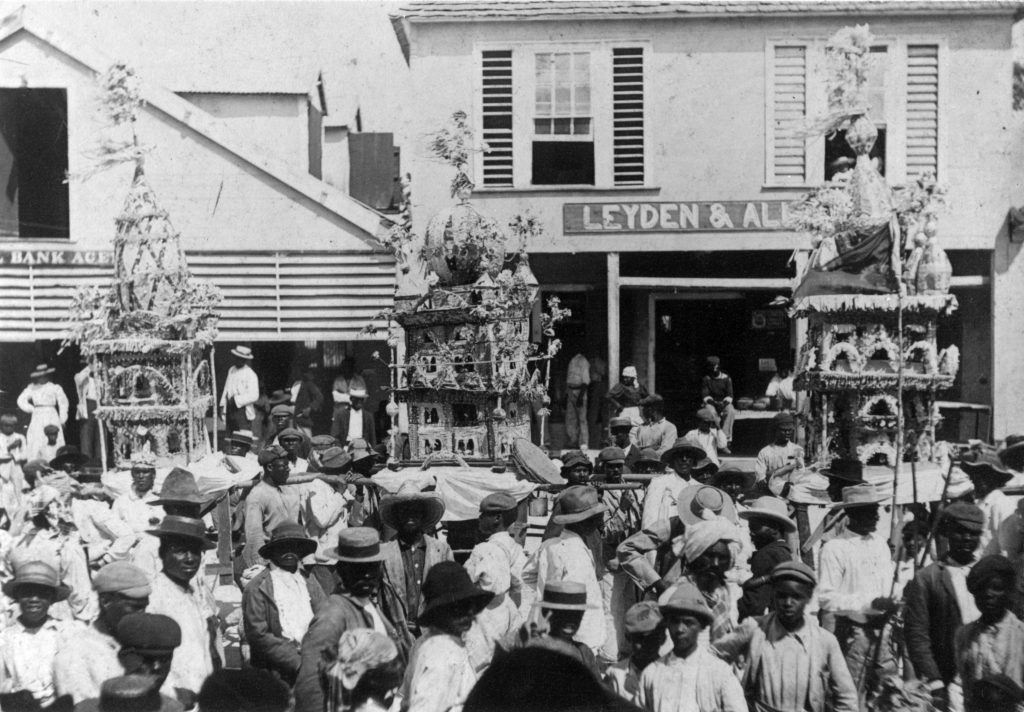

Writing in 1922, Martha Warren Beckwith and Helen Heffron Roberts reported that descendants of Indian indentured workers in Jamaica observed the Hussay festival, which commemorates the martyrdom of Hasan and Hussain, sons of Ali. On the final day of this festival, a procession of mourners carried a tomb made from bamboo and colored paper:

As most Jamaica Indians are from Bombay (Mumbai), the Hussay follows closely the form of celebration described from that locality. It is regularly celebrated at different times in different parts of the island, the north side holding its Hussay in January or February, Vere in July or early August.

The two writers noted that the Jamaican government forbade Hussay processions in both Kingston and Savannah La Mar.

Currently, only about 5,000 Muslims are in Jamaica out of a population of 2.7 million. There are five mosques in Kingston, Spanish Town, Albany and Port Maria in St. Mary, and Three Miles in Westmoreland. Other places of worship (masjids) are at Santa Cruz, Morant Bay and Negril. They have two basic schools.

Several factors have been put forward as to why the presence of Islam on the Caribbean island is negligible, despite its long history there. In Islam Outside the Arab World, Ingvar Svanberg and David Westerlund asserted:

After the abolition of slavery, Muslims either converted to Christianity, or went back to Africa or to other places in Latin America where there were Muslims, or hid the fact that they were Muslims. Until the last quarter of the present [20th] century, Islam was almost unknown in Jamaica outside the small indentured East Indian Muslim community.

The Islamic Council of Jamaica, formed in 1981, seeks to unite Jamaican Muslims, comprising mainly persons of African and Indian ancestry, and some Arabs.

Among the more well-known Jamaican Muslims are musical artistes Jimmy Cliff and the late Prince Buster, who died in 2016.

Eron Henry’s article, Broadening the mind, freeing the spirit, is under consideration for the 2017 NUHA Foundation Blogging Prize. He is author of Reverend Mother, a novel.